Recent Reads: Karl Ove Knausgård, Patricia Lockwood, Marcial Gala, and some honorable mentions

Most of the last few weeks were spent getting through all 1,155 pages of the final entry of Karl Ove Knausgård’s My Struggle series. For those who are not familiar with the project, My Struggle is the Norwegian author’s attempt to present his life story in writing, in granular detail that is meant to approach something like an authentic experience of human existence. He uses the real names of the people in his life and claims to present real events, which caused quite a stir in the media when the first of the books came out just over a decade ago. His recall is impressive — for instance, in Book One, he spends a hundred or so pages narrating an attempt to score beer for a New Year’s Eve party in his adolescence.

Despite the length of the project, the books are strangely easy and, at times, pleasant reads. His prose is strikingly plain. He has a definite tendency towards cliched turns-of-phrase and idioms that oddly serve the writing at large, and perhaps approach something colloquially authentic. The writing is often slow, dwelling on the clutter and minutiae of daily life, with occasional digressions about art and literature that are occasionally profound, often not, but mostly interesting in that they feel like the kind of real thoughts that one has while walking down the street or sitting at the computer, grasping for something intelligent. Knausgård simply committed these half-baked thoughts to paper, while the rest of us have the sense to let them die.

The first few hundred pages of book six, which I just finished, open with Knausgård preparing to publish Book One. He is sending out manuscripts to all the people that he mentions in the project: relatives, friends, ex-lovers. Emails and phone calls are interspersed with his domestic routine: dropping the kids off at daycare, cooking fish cakes for his family, brushing the kids’ teeth, chats with his wife. The main drama of this section arises when his uncle furiously objects to Knausgård’s depiction of his father’s family, and sends increasingly unhinged emails to the author, his mother, and his publishers, threatening to sue to prevent the book’s publication. All this deeply unsettles our author.

The second section is a 400-page close-reading of a Paul Celan poem about the Holocaust, as well as a deep dive into the life and ideology of Adolf Hitler, as covered by various biographies, memoirs, and in Mein Kampf itself.

The last section returns to Knausgård’s personal life, with his wife suffering a manic episode that lands her in a psychiatric institute and leaves him to care for his three children on his own, putting his project, and perhaps the vocation of writing entirely, in a new relationship to real life. It’s incredibly sad and one of the better passages of the whole project.

Critics have tripped over their own feet trying to decide whether or not these books are good. I can’t sum up all my thoughts on this 3,600 hundred page project here. Frederic Jameson put out an interesting review in the London Review of Books where he wrestles with this question, and talks about the implications of Knausgård’s bent toward itemization. As a way out, in a sort of lame imitation, I’ll just put down some of my half-assed thoughts about Knausgård and My Struggle in bullet points, as if itemized:

To get a grasp on who Karl Ove Knausgård is as a person and a writer, maybe read the travelogue he published in New York Times Magazine. He travels to North America and sees all the sites where the Vikings landed so many years ago. He comes off as an extreme parody of himself in these two pieces. It kicks off with him forgetting that he had lost his driver’s license in Sweden and would not be able to get a rental car. He is socially inept and generally maladroit: on the second day he clogs the toilet and is too afraid to tell the front desk. If Tocqueville or the Icelandic Sagas were vague models for this piece, Knausgård himself more closely resembles Mr. Bean.

I still think book one is the best of the six volumes. It deals with the fear he had of his father as a child, his parents’ divorce, and his father’s death due to alcoholism. The book ends with Knausgård and his brother, Yngve, cleaning up his grandmother’s house, where his father died and spent the last period of his life in a tragic, codependent relationship with Karl Ove’s grandmother. The house is covered in trash and the sad remnants of his life, both bodily and otherwise. It’s one of the more viscerally depressing things I remember reading. Book one is probably more traditionally novelistic than some of the other entries, it can be read on its own if you don’t want to commit to the whole series.

Karl Ove Knasgård is not a good person. He seems to know this and he is willing to show his ass, and I think this is why people are drawn to him. It doesn’t absolve him, and he seems to realize this, but maybe it makes him interesting to people.

I’m not convinced of this thought myself, but it feels often that whatever subtext there is throughout My Struggle is incredibly thin. For example, where the narrators of other books may act in ways that betray an oedipal complex or castration anxiety, Knausgård will do the same and then practically say, “I suffer from castration anxiety”. Maybe there is something endearing about this.

The Paul Celan close-reading was brutal, with pages upon pages dedicated to breaking down the different implications of pronouns like I, we, they, you, it. I tried to just let it wash over me, but somewhere in these weeds I developed a strange twitch in my left eye that still has not gone away completely.

The Hitler part of the second part is a bit more interesting, or at least readable, but I don’t think it really arrives anywhere. I can’t decide if I appreciate the attempt to go into it, if it takes the title of his project somewhere beyond gimmick, or if he should have just left it alone. If you decide to read this book and aren’t feeling the Hitler section, you might as well skip it.

It makes perfect sense that My Struggle would become a sensation in a world in which The Sims was also so popular. So much time spent reading about the most rote aspects of daily life; so much time spent playing at the rote aspects of daily life. There is a kind of flattening in both The Sims and My Struggle, which Jameson suggests is the consequence of a tendency toward itemization. Life’s milestones are hardly ever experienced as such, ten minutes later a toilet somewhere will need to be fixed. There is a realism to this, but also something anhedonic about it as well.

A second part of this thought: it was fun, at times, to think of Karl Ove as a kind of tragic, horrifically sentient Sim. The smart yet predictable nature of his digressions and interior life somehow play into this little exercise. I can imagine him crying out in desperation when his need meters turn red.

The copy of book six that I had was a library copy, and someone put post-it notes in it every few hundred pages saying things like “Keep it up,” or “You’re almost halfway there.” On the last page, there was one that said, "Your struggle is now complete”. I didn’t find these cute or helpful in any way.

I read two other books as well since my last newsletter, but unfortunately, My Struggle has occupied most of my brain’s CPU, so I’m not sure I have much to say about them, though I liked them both.

Before My Struggle, at the beginning of January, I read Patricia Lockwood’s No One is Talking About This. It’s a short novel about a woman whose life is essentially spent online, primarily on Twitter. It’s never fully revealed what it is she does, but it is clear she is the kind of media figure whose professional life and identity are entwined with her online persona.

The first half of the novel is a barrage of short, tweetish paragraphs, some of them about her life, some of them just memes and things pulled from the online zeitgeist. It is incredibly funny and Lockwood’s curatorial eye transforms the internet’s most inane artifacts into beautiful writing. I quickly became depressed reading this though, frightened by my own fluency with the words, phrases, and references that took on a perverse, absurd character when presented in a new context and medium. It was a realization that soured my reading experience, but thankfully this first section gave way to something different just as my patience was about to give out.

The narrator’s sister gives birth to a child with Proteus syndrome, a disease characterized by the overgrowth of bones, skin, and other tissues. The lightness of the first section gives way to an exploration of the disorienting collision of true emotion with social media’s pervasive and all-consuming sense of irony. I think it’s a brilliant shifting of gears, and I think Lockwood does a good job of not getting preachy about phones and the internet — it’s clear she is as immersed in it as anyone. Nevertheless, I couldn’t shake the sensation of having just watched a particularly effective PSA. Upon finishing the book I wanted to throw my phone in the Monongahela.

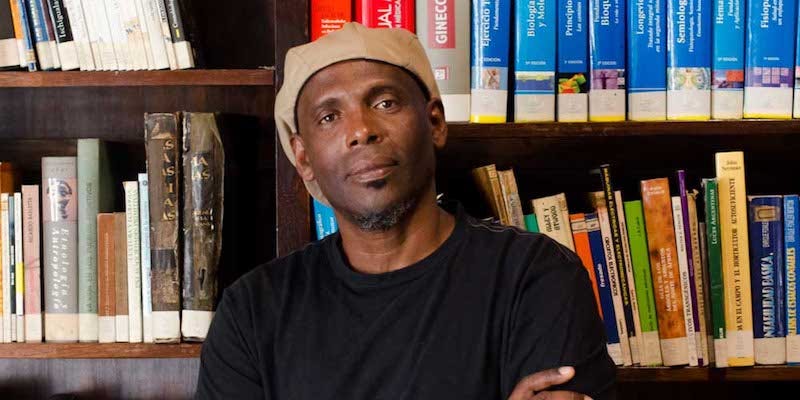

Last week, after My Struggle, I read Call Me Cassandra, by the Cuban writer Marcial Gala. It tells the story of Rauli who either is or believes themself to be the Trojan Cassandra reincarnate. It takes place in the 70’s and 80’s, and every other chapter switches between Rauli/Cassandra’s childhood and home-life in Cienfuegos, and their experience as a soldier during the Cuban intervention in the Angolan Civil War where they are abused by their superiors and supposed comrades. Rauli/Cassandra knows when their own death is coming, is able to see when the people around them are going to die, and is occasionally visited by the likes of Athena, Apollo, and other Greek gods.

Questions of race and gender — of whiteness and blackness, masculinity and feminity in Cuba — are ever-present undercurrents and Gala is able to play with these issues by moving his characters around, from Cuba to Angola and back again. The premonitions of death and the playing with Greek mythology are all interesting elements that keep the plot moving along nicely and the effect of Rauli/Cassandra’s predestination gives the narrator a curious, almost detached quality that makes the abuse inflicted upon them seem almost mechanical, yet unbearable nonetheless. But there are a lot of books with detached narrators, and books that play with the Greek classics, and I wonder how this one will stack up in my memory a month or two from now. Ultimately I think I preferred Gala’s earlier book, The Black Cathedral. I don’t remember the finer details of its plot, but it had a freneticism that has stuck with me.

Before I go, a brief mention of something I read online. The Paris Review recently published “Teonanácatl” on their website, a crónica by the Chilean writer Alejandro Zambra. It is about the author’s experience taking shrooms to treat debilitating cluster headaches and accidentally taking too much. It’s a fun, light piece. I have a soft spot for Zambra — along with Bolaño, he is one of the first writers I was able to read in Spanish. His novellas and short stories are all narrated in a casual, conversational voice, great for people who struggle with the mazier, more baroque language of older writers. This piece also tipped me off to the fact that Zambra is the husband of Jazmina Barrera, whose On Lighthouses was also a thoroughly pleasant read. On Lighthouses is a kind of Sebaldian travelogue about visiting lighthouses throughout the world. Barrera has a new book coming out soon in Linea nigra: an essay on earthquakes and pregnancy. I look forward to reading it.